Why Smart People Keep Ignoring Smart Device Security: The Psychology Behind IoT Blindness

After this week's podcast revelation about the marketing agency losing client files through an unsecured printer, my inbox has been full of variations on the same question: how do intelligent business owners with otherwise solid security miss something this obvious?

The answer isn't comfortable, but it's important: IoT security failures aren't about a lack of intelligence. They're about systematic psychological blind spots that affect everyone from small business owners to government departments.

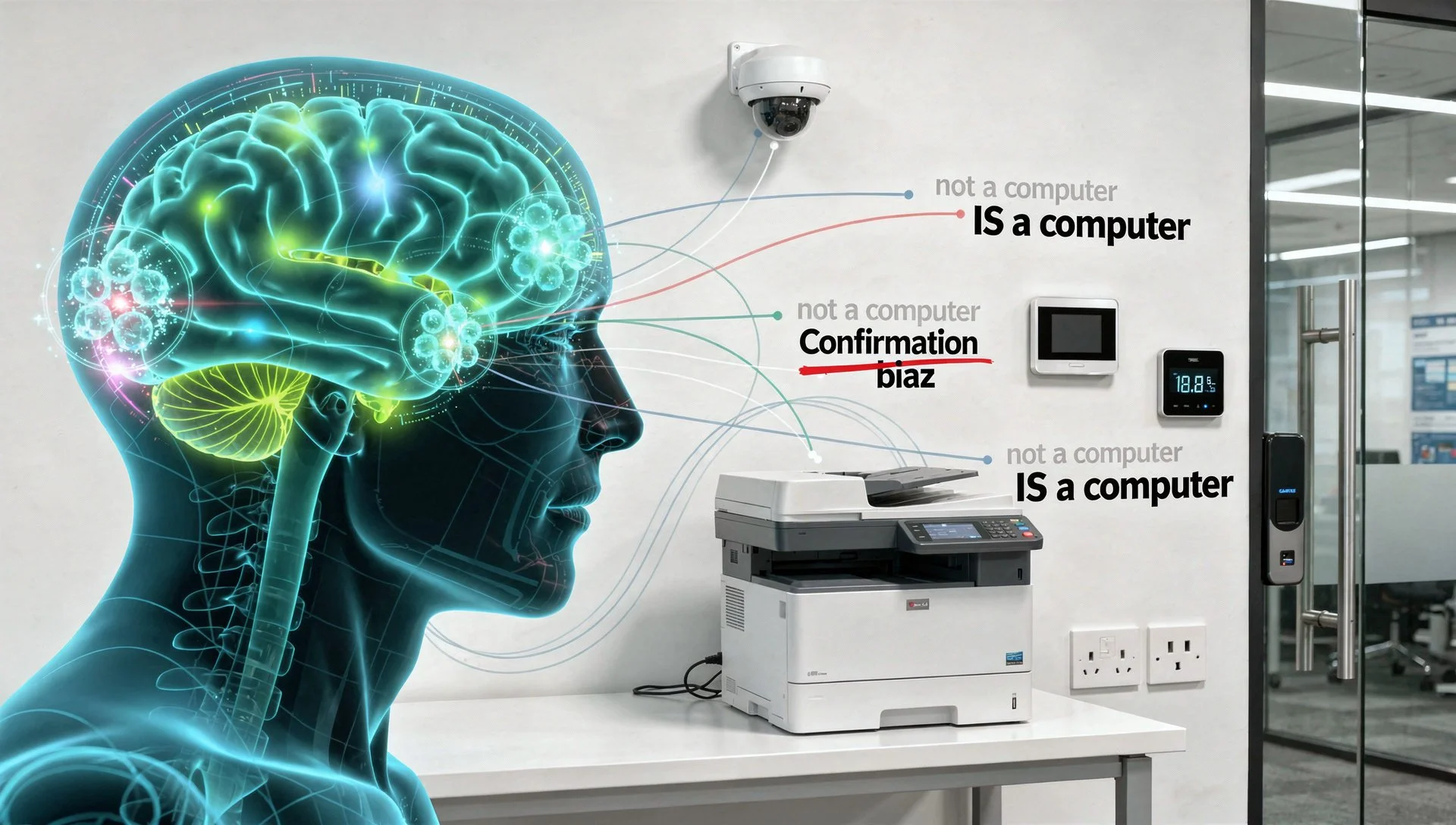

The "It's Not Really a Computer" Cognitive Bias

During my time at as an HMG Cyber Analyst, I watched this pattern repeat itself across organisations of every size and sophistication level. Brilliant people who would never dream of leaving a server unsecured routinely ignore printers, cameras, and thermostats because these devices don't match their mental model of "computer."

This is what psychologists call categorisation bias: we make security decisions based on what we think something is, not what it actually does.

A printer sits in the corner and prints documents. It's office equipment, not IT infrastructure. A thermostat controls heating. It's facilities management, not network security. A camera records footage. It's physical security, not cyber defence.

The cognitive categorisation happens before conscious security assessment even begins.

This isn't stupidity. This is how human brains efficiently process thousands of daily decisions by using mental shortcuts. We categorise objects by their primary function and apply appropriate decision frameworks automatically.

The problem? Attackers don't share our categories.

The Distributed Responsibility Trap

The marketing agency case study reveals another psychological factor: diffusion of responsibility.

Nobody owns IoT security because everyone assumes somebody else owns it. The IT team focuses on computers and servers. Facilities management handles thermostats and door locks. External contractors install CCTV systems. Office managers purchase printers.

When responsibility is distributed, it effectively disappears.

This isn't new. Social psychologists identified the bystander effect decades ago: the more people present during an emergency, the less likely any individual is to help because they assume someone else will take action.

IoT security suffers from organisational bystander effect: multiple potential owners means no actual owner.

The printer in the case study? Purchased by office management, installed by an external technician, and maintained by nobody. IT knew it existed but considered it "just a printer." Office management knew it existed but considered it "an IT thing."

Result: a £300 device with default credentials defeating a £15,000 security investment.

Security Theatre vs Security Substance

Here's the uncomfortable truth from someone who's spent years analysing security failures: humans are terrible at assessing actual risk but excellent at performing security theatre.

We implement visible security measures that make us feel protected, whilst ignoring invisible vulnerabilities that actually matter.

The marketing agency invested in firewalls (visible, impressive, everyone knows they're important), endpoint protection (measurable, generates reports, demonstrates action), and hardware authentication keys (physical objects that feel like real security).

They passed a security audit that checked all the visible boxes: firewalls configured correctly, endpoint protection deployed properly, and authentication requirements met.

But the audit didn't check the printer because auditors also suffer from categorisation bias.

This pattern extends beyond IoT security. We implement complex password policies whilst ignoring social engineering vulnerabilities. We deploy expensive intrusion detection systems whilst leaving default credentials unchanged on network devices.

Humans naturally gravitate toward security measures that are visible, measurable, and familiar, whilst avoiding those that are invisible, distributed, or unfamiliar.

The Comfort of Completed Tasks

There's another psychological factor at play: completion bias. Once we've "done security" by implementing visible measures, we psychologically mark the task as complete and resist reopening it.

The marketing agency had completed its security project. They'd invested £15,000, passed their audit, and ticked all the boxes. Psychologically, security was done.

Suggesting they still had vulnerabilities would require admitting the completed project wasn't actually complete, creating cognitive dissonance.

So they didn't look for additional vulnerabilities. They didn't question whether every connected device was secured. They didn't challenge the assumption that passing an audit meant being secure.

This isn't unique to them. It's universal human behaviour. Once we've invested significant resources in solving a problem, we resist evidence that the problem remains unsolved because accepting that evidence requires psychological discomfort.

The Asymmetric Knowledge Problem

From the attacker's perspective, IoT devices are obvious targets. They maintain databases of default credentials. They scan for exposed devices. They specifically target the equipment businesses forget about.

Attackers don't need sophisticated social engineering when they can try admin/admin on every printer and camera on the internet.

From the defender's perspective, IoT devices are barely visible. They're not computers, they're just equipment. They're someone else's responsibility. They're not included in security assessments.

This knowledge asymmetry creates systematic vulnerability. Attackers know exactly where to look. Defenders don't even know they should be looking.

Security requires closing knowledge gaps, but you can't close gaps you don't know exist.

Breaking the Psychological Pattern

So how do we fix systematic psychological blind spots? By acknowledging them and designing compensating mechanisms.

First: Recategorise Everything with Network Connectivity

Stop thinking about printers, cameras, and thermostats as office equipment. Start thinking about them as computers that happen to print, record, or control temperature.

If it has an IP address, it's a computer. Full stop. Apply computer security thinking to everything with network connectivity, regardless of its primary function.

Second: Explicit Ownership Assignment

Combat diffusion of responsibility by explicitly assigning ownership. Every device needs a named individual responsible for its security, updates, and maintenance.

Document this. Make it visible. Review it regularly. Don't assume responsibility exists. Create it explicitly.

Third: Include Everything in Security Assessments

Audits and assessments should explicitly scope IoT devices. If your security review doesn't check printers, cameras, and thermostats, it's not actually reviewing your security.

Require comprehensive device inventories as audit prerequisites. No exceptions.

Fourth: Regular Reality Checks

Schedule quarterly reviews specifically focused on devices that "aren't really computers." Force yourself to periodically challenge the categorisation bias.

What new devices have been added? What equipment did contractors install? What devices are connected that weren't in last quarter's inventory?

Government Lessons for Commercial Reality

During my days as a civil servant, I watched government departments struggle with identical issues. Sophisticated security teams with impressive capabilities repeatedly miss basic IoT vulnerabilities because "it's just a printer."

The solution wasn't more security expertise. It was better psychological awareness and systematic processes to compensate for predictable human blind spots.

The most successful organisations didn't try to eliminate categorisation bias (impossible). They acknowledged it and designed explicit compensating mechanisms: mandatory device inventories, assigned ownership, and regular IoT-focused reviews.

The Takeaway

The marketing agency isn't stupid. Their security investment was legitimate and addressed real risks. Their audit was conducted by qualified professionals following industry standards.

They failed because they're human, and humans have systematic psychological blind spots that attackers exploit.

Understanding the psychology behind IoT security failures doesn't excuse them, but it does explain them. More importantly, it points toward practical solutions: recategorise network-connected devices, assign explicit ownership, include everything in assessments, and regularly challenge your assumptions.

Your printer is a computer. Your camera is a computer. Your thermostat is a computer. Start treating them that way.

Or wait for the breach to teach you the lesson the expensive way.

| Source | Article |

| NCSC Human Factors | Human Factors in Cybersecurity |

| Cognitive Psychology Research | Categorisation Bias in Security Decisions |

| Social Psychology | The Bystander Effect in Organisations |

| Episode 30 Podcast | The Devices You Forgot Were Computers |